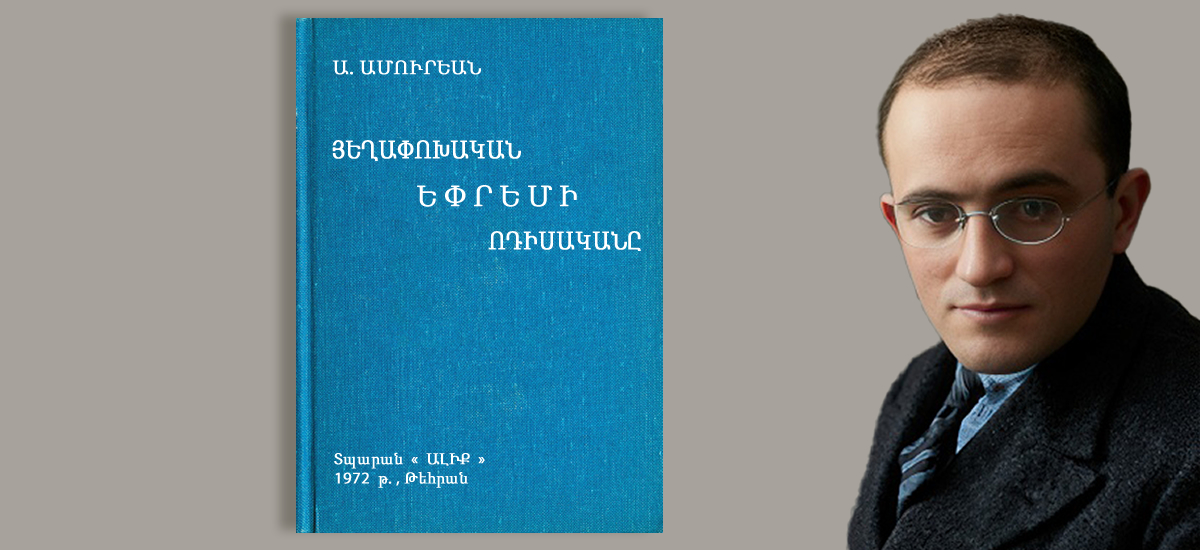

Under this number and this column heading, we begin the presentation of the memoirs of the well-known ARF veteran Andrée Der Ohannessian (A. Amurian). This volume of memoirs, titled "Pages of Life" and bearing the inscription "From Childhood until 1936," has been made available to us by the ARF Bureau. Due to understandable journalistic necessities, we are publishing the manuscript by selecting excerpts from it. The period of this first excerpt is the winter of 1917-1918.

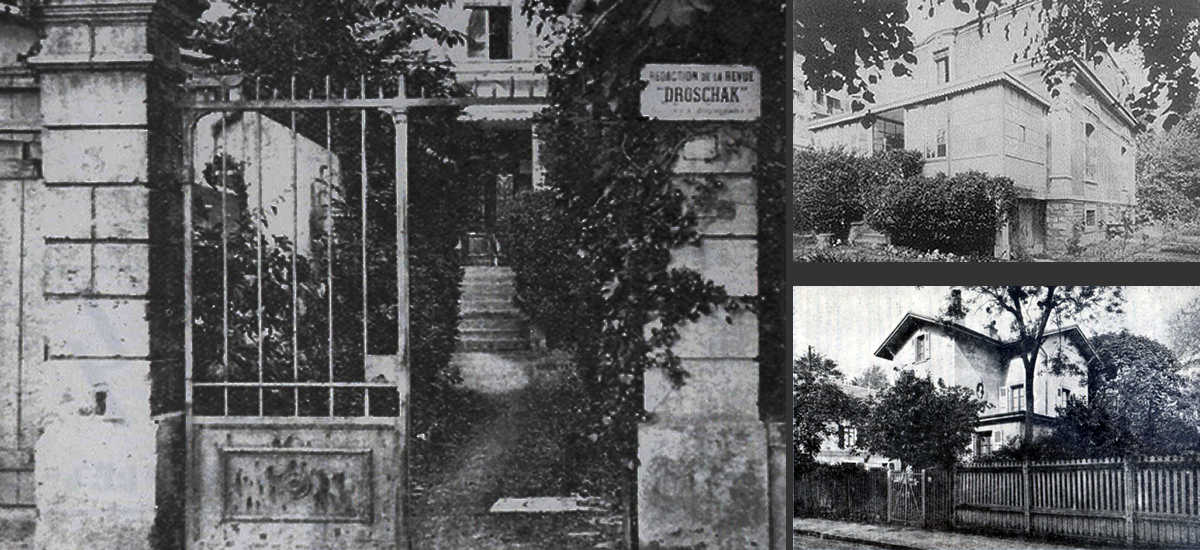

This column, aspiring to the publication of unpublished works or the re-evaluation of "Old Pages," will be a permanent presence in "Droshak."

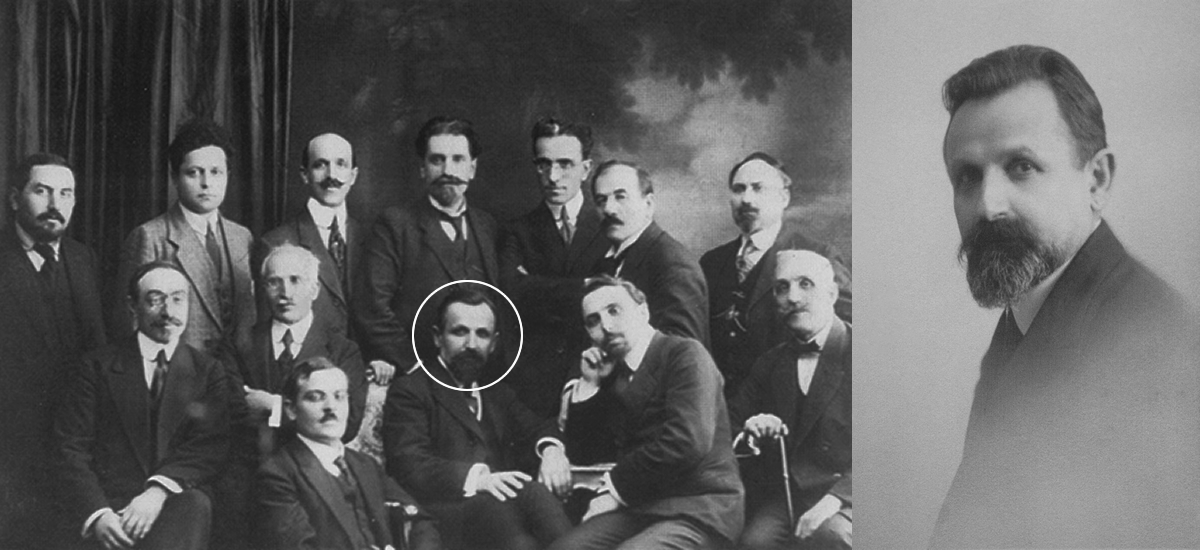

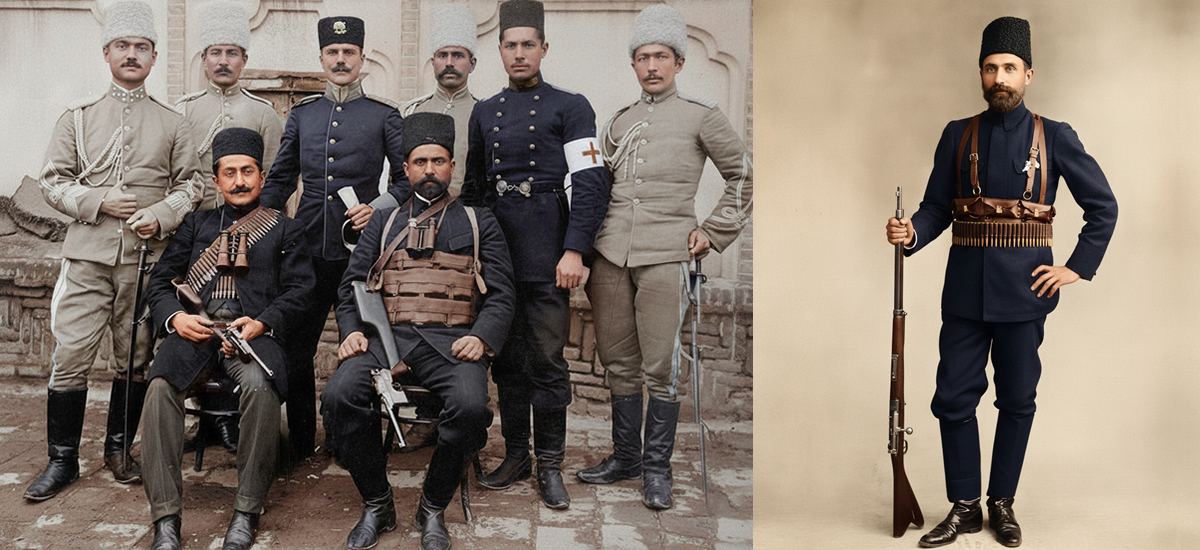

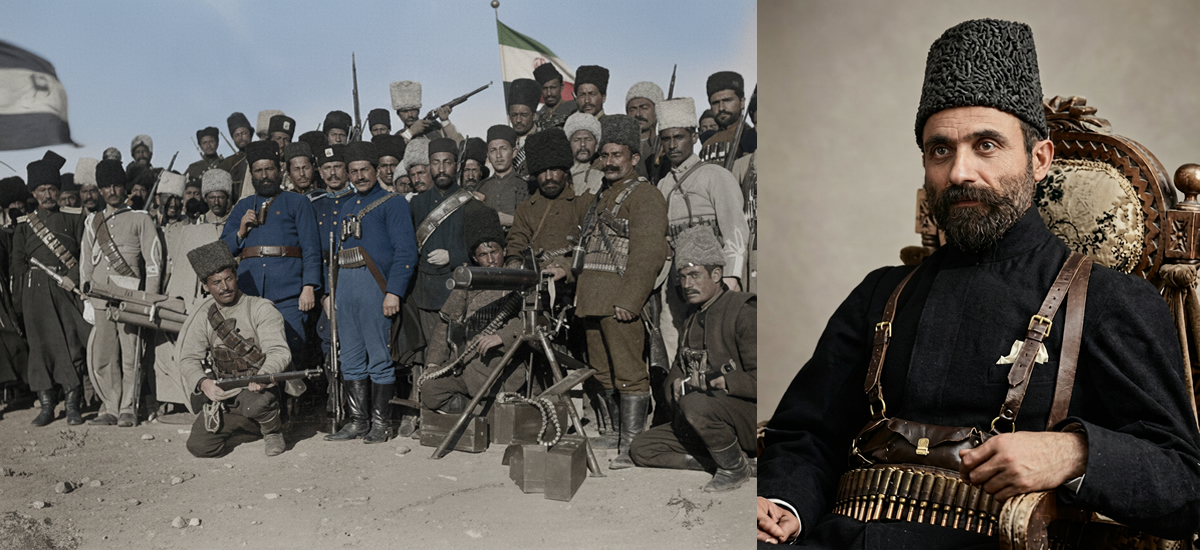

1. ANDRE AMURIAN - A LEGENDARY VOLUNTEER

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 2, May 14, 1986, pp. 72-73.

I lay for three days at my maternal aunt's house in Tiflis, then got up. They wanted two delegates from two grades of the seminary for the Armenian Student Congress, which was to take place in Baku; the boys from our class had elected me, and from the upper class, they had elected Vartan Hovhannisyan (V. Astghuni); both of us were from Tabriz.

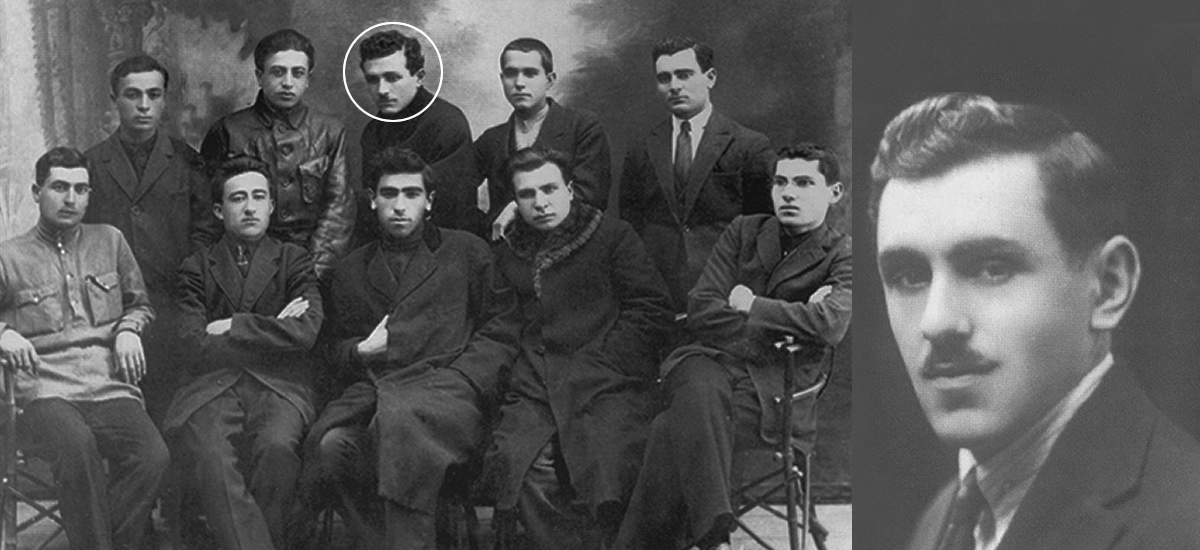

I was to meet comrade Hamo Ohanjanian's son, Monia Ohanjanian, regarding the trip to Baku. I went to Monia's house. He received me warmly. Monia was a seventeen-year-old boy, my age, handsome, with a Greek profile, his hair combed to one side. He was a Russian speaker (from Hamo's first wife, who was Russian). He was wearing the uniform specific to the Lisitsian gymnasium. Monia's room was very simple: a few books and notebooks on the table, one or two sports equipment in the corner.

We spoke in Russian. Monia said that Vartan and I should go to Baku, and he would also come with his friends.

The congress began. The central figure was Monia. Also notable were Yegia Chubar and Amatuni* (in 1926-27, he was sent to Paris by the Bolsheviks; he edited the "Yerevan" newspaper and attacked the ARF. Amatuni also became an important figure in Soviet Armenia. In the end, the Bolsheviks "liquidated" both of them... A.A.). While giving a speech, Chubar even quoted those lines from A. Isahakian's poem which say: "For a thousand years, and even more, the Tatar has knelt on our chest." That's what they said, and in the end, they became Bolsheviks.

During the proposals section, I asked for the floor and dictated that Armenian students must study our history well, read our chroniclers—Movses Khorenatsi, Yeghishe, Ghazar Parpetsi, etc., become aware of our national demands, and feel proud of our past.

The audience applauded, while the organizers treated it with disdain. They had a similar attitude when greetings telegrams were to be sent; I proposed also sending a telegram to Etchmiadzin, to the Catholicos of All Armenians. The majority was in favor.

The greeting speech was given by Simon Hakobyan, the editor of "Arev," the ARF organ in Baku.

During the breaks, Armenian young ladies hosted us with pastries, tea, and lemonade. They spoke Armenian in their parents' dialect, mixing in Russian.

During free times, we went to the Baku port. For the first time, we saw hydroplanes; they were constantly flying.

We returned to Tiflis from the Baku Armenian colony. The situation on the Caucasian front was chaotic; the Russian troops were retreating like a headless herd, they were heading "home." The National Council and the ARF were rising to form national military units and send them to the front.

In those days, Monia Ohanjanian convened a student meeting in the hall of the Tiflis City Administration. The hall was packed. Monia was sitting behind the table; next to him was student Hrant. Both were ardent patriots.

Monia explained the political situation, then called for students to volunteer to go to the front. We all agreed, appreciating Monia's proposal.

The call of Dr. Jakob Zavriev, addressed to the students, to volunteer and depart for the front, resounded.

My close classmate, Stepan Shahgeldian (from Kishinev) had briefly gone to Erzurum and then returned. I had him tell me about the front and Turkish Armenia. I couldn't get enough of listening. I told Stepan that I was volunteering. He said: "I will go with you to the Erzurum front again." I was happy.

Dr. Artashes Babalian was registering the volunteers; when I was about to go up to his office, I met Mushegh Santrosian, a graduate of our seminary. He complained: "Brother, what kind of man is this Babalian?" They had had an argument and Santrosian had left.

When I entered, Babalian was on the balcony watching the street traffic. He came and asked what I wanted. I said I had come to register as a volunteer, that I was from the seminary.

- We will send you to Khnus, to Colonel Samartsev's headquarters, as a clerk. You will receive one hundred twenty rubles per month...

I cut him off, saying that I was volunteering, not to be an official, receiving money...

- Why, will the money burn a hole in your pocket?

- Yes, - I said, - an official is one thing, a volunteer is another...

Babalian conceded, wrote two papers, one for my insistence, the other to receive clothing and boots from the military depot.

The city of Sarighamish was a kilometer away from the station. There was no means of transport; we had to walk. But it was a dark night and dangerous; Russian (deserter) soldiers could attack us. At that moment, as if from the sky, student Hrant appeared near us. "Boys," he said, "form two lines, I will walk behind you. I have a Browning pistol, I will protect you."

We did just that and, slipping, groping in the dark, we walked to the Sarighamish headquarters, where we were received by Hnchakian captain Pandukht, who was the head of the headquarters.

The so-called headquarters were two spacious shops, with crates lined up against the walls containing dynamite and bombs. Also a few rifles leaning against the walls. Behind the shops was a large courtyard, like a caravanserai.

(...) We were to depart for Erzurum by military truck. We were joined by the wife of the well-known ARF youth leader in the Caucasus, Hampig Cholakhian, Asheen Cholakhian, who was wearing a fur military jacket and sapogi (high boots) on her feet. Her hair was cut short; her face was not beautiful.

She immediately became friendly with Stepan and me; she had the truck's tarpaulin pulled down so the cold wouldn't penetrate inside too much.

Anyone who hasn't been in Western Armenia cannot have an idea of the frigid winter there, 35-40 degrees below zero, sometimes even more. The mountains and plains are covered with a thick layer of snow and ice. The surface of the rivers is covered with ice; people cross the river on foot and on horseback. For the months I was on those fronts, I didn't see the sun. From Köprüköy to Erzurum, we didn't see a single tree. Only Sarighamish is forested, beautiful....

The cold penetrated inside; it was already cold inside too; the cotton sewn into our jackets and military trousers and coats didn't help, nor did the woolen socks.

Before reaching Erzurum, we had to cross the Deveboynu mountain pass. "God forbid we get caught in a blizzard, or we'll be buried under the snow," our companions said. Fortunately, it went well, and we, frozen and tired, reached Erzurum, where we entered through a thick wall's gate, the path from which went upwards for a short distance.

We got off at the door of the Erzurum military headquarters. As soon as we entered, we met our seminary supervisor, Yervand Hayrapetian, who was engaged in orphan collection work on behalf of the Cities Union. He received us with love, feeling proud that seminary students were volunteering in large numbers. He said that for now we should sleep in the military barracks and eat at the headquarters.

We went out to stroll around the city. Snow-winter, sleds were operating, pulled by one horse. Everything had a military look. We met our classmates Yeghishe Zarutian, Yervand Zakarian, Western Armenians Hovakim Guloyan, Armenak Srapian, Haykaz Ghazarian from Vagarshapat, Hovhannes Manukian from Akhalkalak, Nahapet Kurghinian from Ashtarak, all from our class.

The next day, our comrades took us to see the Armenian church and the Sanasarian School. In the courtyard of the Sanasarian School, we saw the bust of the benefactor Sanasarian. The Armenians of Erzurum were absent, looted, exiled, massacred; the institutions and houses had become owls' dwellings. Our hearts bled...

We had a lot of free time; we asked the boys what they were doing; they said they were mostly engaged in target shooting. We gladly joined them; we hadn't fired a rifle yet.

Our training proceeded quickly; we became well-trained in marksmanship.

2. FROM THE COLLAPSE OF THE TURKISH FRONT UNTIL MAY 28

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 3, May 28, 1986, pp. 14-15 (122-123).

My concern was the front. The front was a thousand kilometers long, from Trabzon to the Persian border; its depth was 300-400 km. Against the retreating 300,000 Russian troops, we had barely 20-25,000 Armenian soldiers, fedayis, and volunteers; this was a very small force against the Turkish army of at least 200,000.

Therefore, our retreat was inevitable.

With this thought, I wrote a letter to the Armenian National Council in Tiflis, proposing that part of the weapon depots be moved to the rear, so they wouldn't fall into the hands of our enemy. I received no answer. (Years later, in Tabriz, when I told Nikol Aghbalian about this, he said: "Imagine, I proposed the same thing in Yerevan, that part of the depots be moved to the New Bayazet region, to the rear, but no one listened to me").

(...) East of the village of Köprüköy, barely a kilometer away, is the historical bridge, under which the Araks flows, covered with ice in those days.

(...) I often went alone, stood on the bridge, surrendering to sad thoughts, because I felt that one day we would lose these our ancestral lands due to lack of strength, and my tears flowed...

On the other side of the bridge was the former Armenian village called Yaghan, all of whose inhabitants had been massacred by the Turks. The Armenians of the village of Köprüköy had also been massacred, their houses destroyed, even the logs taken away, carried off...

(...) In the evenings, Tsaghikian, Vartzakep, and the Nersisian youth Gevorg were often absent. One day I asked Gevorg where they were going. He didn't hide it; he said they were hunting Turkish spies in the rear; then he told the following: "We caught a giant Turkish spy, he was denying it; we searched him, found letters and papers on him; he was a spy. We demanded he confess, he refused; the comrades fired and wounded him in two places; he was kneeling, wouldn't fall; he said, 'Finish me off, so I can rest,' I approached him and emptied my pistol into his temple, he fell, died...."

Once, when there was talk about that, I said that in such cases the spy should be handed over to a military tribunal, and then dealt with. "André," said Vartzakep emotionally, "fifty people from my family were massacred by the Turks, they were not spies; do you want us to deal with a Turkish spy through a tribunal...?"

One evening, a passenger car stopped in front of our headquarters. "It's Andranik," they said; we were all excited. The arrivals were Andranik, Dr. Jakob Zavriev, a Russian general, and Hamlik Tumanyan (Hovhannes Tumanyan's son). I had seen Andranik passing through Yerevan Square in Tiflis; I had seen Hamlik at the Gevorgian Seminary, where he came to the class above us, stayed one year, and then didn't come again.

Everyone gathered around Andranik to see what the Pasha was saying. Andranik had rheumatism; they lit the stove well, and also put a hot water bottle at his feet. They began to talk; every word of Andranik's was taken as a command. Andranik spoke about the defense of the front, the retreat of the Russian troops, the grave situation created for the Armenians....

(The fall of Erzurum will signal the general retreat. With the wave of retreating army personnel and people, the young volunteers will approach the Russo-Turkish pre-war border line and Sarighamish).

We walked through the snow, up, down, through blizzards and storms; finally we reached near Karaurgan. About 200-300 steps remained to the barracks when we fell, exhausted, on the snow, and slept...

Someone is shaking us, saying: "Boys, you will freeze here, get up, let's go..." It was a young Armenian soldier who interrupted our very sweet sleep. He took us by the arm and almost dragged us towards the barracks.

The barracks were warm; the Armenian soldiers fed us. In Sarighamish, we didn't know where to stay, when seminary student Hovhannes Gyulnazarian from a higher grade came out to meet us and led us to the barracks where he was staying. (...) Right at the entrance of the headquarters, on both sides, two horses had frozen, turned into statues in a rearing position... A sculptor could not have done a more successful job than nature had done. In those days, the poor horses, abandoned by the troops and without food, emaciated, wandered the streets stumbling and would fall somewhere, die....

We were near the headquarters and were admiring the frozen, rearing horses with amazement, when Monia Ohanjanian and student Hrant appeared. We talked about the situation; I expressed dissatisfaction about the retreat and the leadership's inability to organize resistance. Monia said that there had been resistance in Erzinka and that Hrant had also been wounded. Later I learned that Monia had been awarded a medal for the battle of Erzinka, but he himself didn't tell me about it.

I immediately softened. "Seriously?" I said, and filled with respect towards Hrant; "Where was he wounded?" I asked. Hrant showed the area of his right hip; the bullet hole was still on his trousers.

- Monia, can I also be with you? - I asked.

- It depends on the headquarters' order, - said Monia.

I entered the headquarters. Yeghishe Zarutian was there; he approached me and said: "You and I are assigned to transport the party's weapons from Sarighamish to Kars."

One or two days later, we arranged the weapons on the bottom of a cart, covered them with plenty of dry hay, and set off for Kars with four people.

(...) In Kars, Yeghishe and I took the party weapons and handed them over to representative Valad Valadian. Soldiers, refugees, the alarming state of the locals; we didn't know if Kars would withstand the Turkish assaults...

We presented ourselves at the headquarters; they told us to go to Alexandropol, the headquarters would arrange things there.

In Alexandropol, we heard that the Turks had reached Sarighamish. Our souls were gloomy; would Kars hold? If it didn't, then it would be Alexandropol's turn next. And then? Alexandropol was a crossroads: to the south Kars, to the north Karakilisa and Tiflis, to the east the road leading to Yerevan... The Turk aimed to crush, destroy Eastern Armenians as well, clear the way to Baku, to seize the oil wells, to realize the Pan-Turanian empire.

At the Shamkhor station, local Tatars had attacked the retreating Russian troops and massacred them; thereafter, the retreating Russian troops were clearing the way towards Baku, and then Russia, with machine guns mounted on the train cars.

The desertion of Armenian soldiers caused us anger. The Russian soldier didn't care; he left the front and went home. But the Armenian? After all, "Hannibal was at our gate." But there were fedayis and soldiers who were ready to sacrifice their lives, and that was our consolation.

We presented ourselves at the Alexandropol headquarters; here too they told us to wait for their orders.

We heard that Andranik had come to Alexandropol with his soldiers and a group of Western Armenian refugees. Then we heard that he had asked the headquarters for weapons and ammunition, they didn't give them, so he had a weapons depot opened and took the weapons. Later we also learned that Andranik had left for Karakilisa with his group.

We received news that Kars had fallen AND the Turks were advancing towards Alexandropol.

When we presented ourselves at the headquarters, they ordered us to depart for Karakilisa. "Why don't we stay here, the Turks are advancing, we will fight," I said. "Your need is greater in Karakilisa," they said. "Stepan," I turned to my comrade, "they are sparing us, because of our age." "Let's do whatever they order," said Stepan.

I had passed through Karakilisa by rail before; every time, the air was humid, often rainy.

We also presented ourselves at the headquarters there. "We are putting you on the telephones," they said. "We are ready to fight in the ranks, we have rifle training," I said. "You know, young men, the fedayis and soldiers know neither regular Armenian, nor even a little Russian. But you are masters of both, therefore suitable for the telephone. The telephone on the battlefield is just as important, perhaps even more, than the role of an ordinary soldier," said the official, disarming us with his reasoning.

Events were unfolding at a dizzying speed. We learned that Andranik had gone up to the village of Dsegh, the Turks had approached Alexandropol; fugitives, refugees. Karakilisa was teeming with deserting soldiers, crowds of peasants; everyone was gloomy, worried. We learned that General Nazarbekov had been appointed commander of that front; he was a Russian speaker, but a warm patriot and endowed with experience in battles and engagements. And General Nazarbekov had proposed that Andranik participate in the battle, but Andranik had argued that he didn't have a sufficient quantity of ammunition. It was said that Andranik had about two thousand fighters.

And so, on May 24, the mountains and forests of Karakilisa echoed with the roar of rifles, machine guns, and cannons. We, on the telephone, were located behind the fighters and transmitted the given orders to the hills designated by numbers. We were extremely careful to convey the orders accurately.

The Turks' aim was first to capture the railway line. Our positions were located both to the left and, especially, to the right of the railway line. At night the fighting would stop a bit, but sleep wouldn't come to our eyes; we would doze off, suddenly wake up, grab the rifle.

We heard that the Turks had moved troops by rail towards the Shamkhor-Baku route; but our men held the positions on the right side of the railway firmly. That alarm lasted three days, with the earth and sky roaring. The Armenian fedayis and soldiers fought bravely; it was a life-and-death struggle.

Rumors circulated that our men had successes on the Bash Abaran and Sardarapat fronts, that the Turks had not succeeded in their main objective... The rumors became more and more accurate, creating enthusiasm.

But as far as I know, the Battle of Karakilisa cannot be considered a complete victory, because the Turks had succeeded in moving troops in the direction of Baku.

After the Battle of Karakilisa, we learned with great sorrow that our incomparable Monia Ohanjanian had fallen on the front lines... I couldn't close my eyes all night; I remembered my first meeting with him in Tiflis, then at the student congress in Baku, then again in Tiflis, in the City Administration hall, when Monia called for volunteering; then in Sarighamish, in front of the headquarters, my last meeting with him....

MEMOIR

3. ACTIVITIES IN THE PARIS-ARMENIAN COMMUNITY: PART 2 OF THE 1920s [A.]

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 11, September 17, 1986, pp. 16-18 (384-386).

I submitted my diplomas from the "Gevorgian" seminary and Prague University to the Sorbonne University with an application. A week later, my application was accepted.

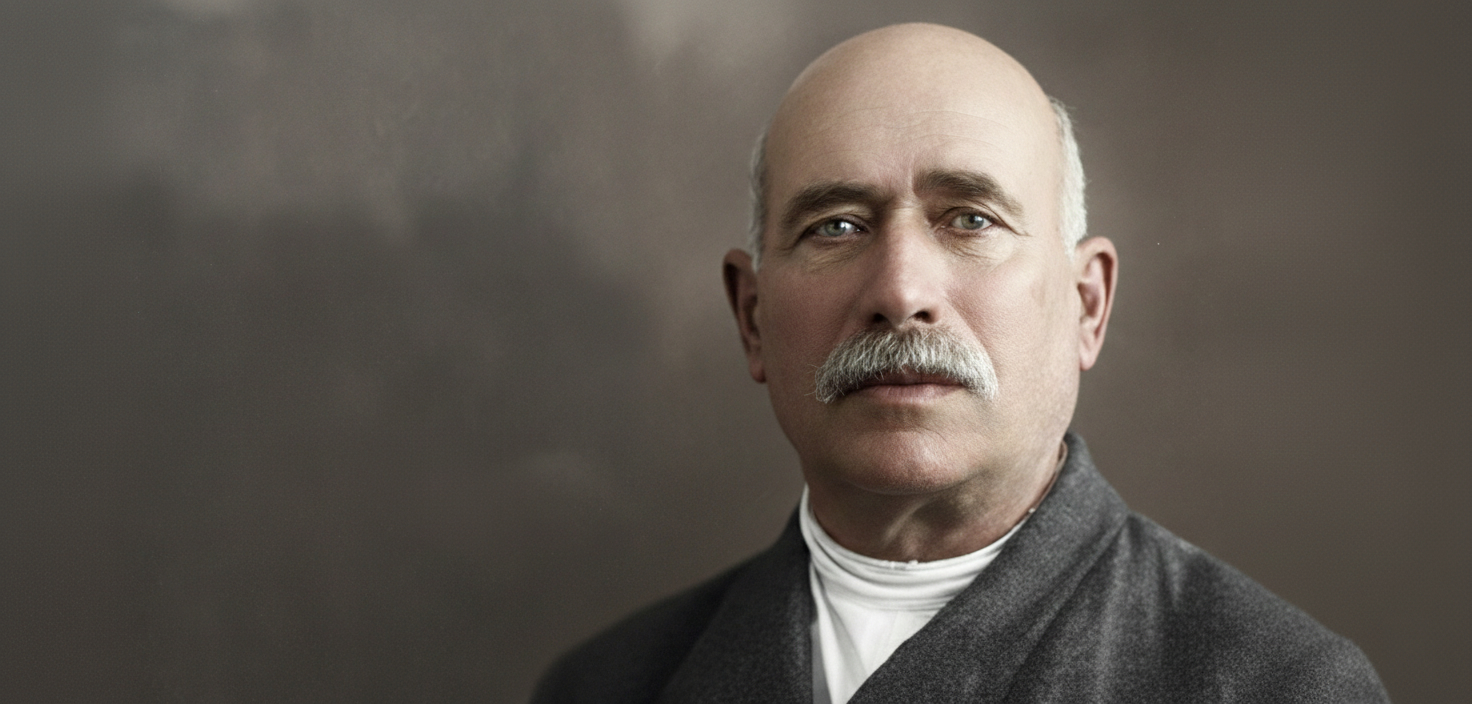

The seminary diploma was very respected in all European universities, and many Armenians in Europe were receiving their university education, for example, seminary graduates: Vahan Soren (graduate of Berlin University), Arshak Jamalian, also, Avetis Aharonian from Switzerland; Rouben Der Minasian from Switzerland and many others.

I started learning the French language with particular love and especially didn't miss the lectures of the famous economist-cooperativist Charles Gide.

Avetis Aharonian had secured a stipend for me from an Armenian individual named Dikran Khan Kelekian.

Indeed, Aharonian had a special affection for Iranian-Armenians.

- André, - Aharonian said one day, - you will be my personal secretary. You know my handwriting is almost illegible, I need someone who writes clearly, I will dictate, you will write.

And so it was. He himself would tell about Andranik, I would write it down. Later I proofread his volume "My Book."

Aharonian's wife, Nvart, was the sister of comrade Mikayel Varandian. Her first husband, Zhamharian, had been killed in Shushi, during the Armenian-Turkish clashes. Aharonian had three sons from his first wife: Vartges (he was an editor-activist in America), Vurik and Babik. These two were capable boys, but unruly. They knew Armenian, Russian, French, and Babik also knew English. At one time Aharonian started studying English, saying: -

- My little rascal, Babik, there isn't a word he doesn't know. I ask him for words.

Aharonian had a two-room apartment, one a bedroom, the other a living-dining room. They were small rooms, so the two boys lived in rented rooms. I was the one who took their rent money and paid it; Aharonian would say: -

- If I give it to their hand, as soon as they go out, they'll spend it...

Vartges Aharonian's wife was the poetess Armenuhi Diranian-Aharonian.

I had been fascinated by Aharonian's literature since my student days. His beautiful and perfect, rich Armenian had an influence on my Armenian. I had read his book "In Italy" several times, which is a rich, captivating description of the historically valuable places and monuments of Italy. When I told him about this, he said:

- Imagine, I wrote that book in two weeks.

*

Aharonian related that Ishkhan was seriously ill and had become very emaciated; his heart was sick. We decided to visit him; he lived in the Chaville suburb.

When we boarded the streetcar, all the French people's gazes turned to Aharonian, he had such an impressive appearance; he also had a deep voice and spoke beautiful sentences when talking. He had a typical Armenian appearance. Looking at him, I pictured Vartan Mamikonian; he was a man of the sword, Aharonian was a man of the pen, both warm patriots, exemplary Armenians, with aristocratic traits.

On the way to Ishkhan's, Aharonian prepared me, saying:

- Picture it as badly as you can, so you aren't taken by surprise.

When we entered the room, I was simply shocked....

Nothing remained of that tall, stately Ishkhan; a pile of bones. Sitting in his bed like a chick. Aharonian looked at me, saw I was very emotional, started occupying Ishkhan so I could calm down a bit. Was this the Ishkhan of Khanasor... unjust life.

- Ishkhan, - said Aharonian, - our young comrade André wanted to visit you, he is now settled in Paris.

Ishkhan smiled with pleasure, - thank you, - he said. Then he asked about my uncle, Smbat Melik Vardanian, who had been in the diplomatic corps, in Tehran. I said he was in Tehran, had now opened a bakery.

To this day, Ishkhan is before my eyes: emaciated, skeletal, hunched in his bed.

Barely a month later, Ishkhan died. At the funeral, his wife, Ishkhanuhi (Satenik, Tsaghik) was crying and saying: "I sent him in front of bullets, I didn't feel pain. Ishkhan! Were you to die like this, where are you going?" I saw that comrade Arshak Jamalian wept bitterly. We were all crying at the sight of the death of the self-sacrificing fedayi, the warm patriot.

Another tragedy was that the grave plot had been bought for six thousand francs, and a few years later the plot would have to be bought again, otherwise they would bury another dead person on top of that coffin.... Such is the law, even in a suburb like Chaville.

Jamalian gave the eulogy, on behalf of the Bureau, ending it in tears.

I had read that when Ishkhan and a group of fedayis were besieged in the Derik monastery, Ishkhan's wife, Tsaghik (Satenik), would load the fedayis' rifles, and now I saw that the tip of her shoe was worn out and her toe was visible... I too lived my tragedy from this scene. This is the end of an Armenian revolutionary, I thought, and my convictions were further strengthened within me. After all, I had to go to Armenia. The Armenian revolutionary is reconciled with every difficulty of life and the idea of death.

*

After the 10th General Assembly, the Bureau had assigned Dr. Armenak Melik Barsesian to tour the Armenian-populated cities of France and register party members, form committees, so that a Regional Assembly could be convened and a Central Committee elected. Until then, there was no Central Committee.

At the meeting of the Paris committee, I was elected a delegate to the Regional Assembly.

The delegates to the Regional Assembly were: Arshak Jamalian (on behalf of the Bureau), Dr. Armenak Melik Barsesian, Vahagn Krmoyan, Papazian, Vahan Hambardzumian (former seminary graduate), Hrant Samvel, Benik Miltonian, Shatikian (from Marseille), Abo (Baghdasar) Aboyan, Andranik Der Ohannessian, Grigor Zamoyan and three or four other comrades whose names I don't remember.

Among these comrades, the unpleasant one was Abo Aboyan, who gave the impression of a flattering Jew, always with a smirk on his face. (It was he who later started the so-called "Martkots" movement, which had a factional character and ended in their disgrace; more on this later).

The agenda items, relating to organizational life and the organization of the Armenian colony, were resolved with corresponding resolutions. The turn came for the election of the first Central Committee of Western Europe.

A five-member body was elected: Vahagn Krmoyan, Benik Miltonian, Abo Aboyan, Hrant Samvel, André Der Ohannessian.

Immediately after the assembly, the Central Committee's inaugural meeting took place; Vahagn Krmoyan was elected chairman; comrade Jamalian proposed my candidacy for the secretariat; when I started taking notes from the meeting, Aboyan objected that I was writing in Eastern Armenian, that the minutes should be composed in Western Armenian. He was a factionalist, so I categorically declined; comrade Hrant Samvel was appointed secretary.

After two or three meetings, Vahagn Krmoyan resigned from the Central Committee; when I asked him privately the reason, he said: "I cannot work with that Aboyan..." Aboyan was appointed chairman, and candidate Vahan Hambardzumian was invited to replace Krmoyan.

In those years, the Armenian Bolsheviks in Paris and the provinces were causing provocations to disrupt our events. Comrades recounted that in Paris, at one of our events, they had tried to disrupt it with shouts and distributing leaflets, when Arij Petros alone went out against them and with his tremendous strength grabbed them and threw them down the hall stairs like sacks... One of those who tried to disrupt was the former Hnchakian Ashod Patmagrian, whom Arij Petros also threw down. The event took place and thereafter they didn't try to disrupt our events in Paris.

We took Mesrop Guyumjian as a regional activist for the Western Europe Central Committee; he was a long and smooth orator.

- If the Bolsheviks also try to disrupt our events in the provinces, we must defend ourselves, counter-attack, - Benik Miltonian would say, irritated.

In those years, the Bolsheviks were publishing a newspaper called "Yerevan," to which they had sent Yegia Chubar from Armenia as editor, with whom I had participated in the Baku student congress. In those days, Y. Chubar had begun one of his speeches with "For a thousand years and more, the Tatar has knelt on our chest" (from A. Isahakian), and now he had come to Paris to preach internationalism. I didn't want to meet him. The "Yerevan" newspaper was causing provocations and splitting the Armenian colony.

We sent prominent comrades to the provinces to give lectures. For our event to take place in Lyon on May 2, 1926, the Central Committee sent comrade Avetis Aharonian to the city of Lyon.

On May 2, I bought a French newspaper, entered the metro. Looking at the paper, my eye caught a headline in large letters:

Lyon: - Bloody clash - Disturbance among Armenians...

I immediately went to the Delegation of the Republic, reported what had happened and showed the paper; through comrade Khatisian I asked, via secretary Artavazd Hanimian, to contact our comrades in Lyon and find out what happened. I phoned the Central Committee comrades, and I myself hurried to Aharonian's apartment. At the door I met comrade Mikayel Varandian, showed him the paper and said I had been to the delegation office and asked to contact Lyon by phone. Varandian said: "Let's go upstairs. But let's not let Nvart know about what happened, let's wait for Avetis."

We went upstairs, to Mrs. Nvart. A little later she seemed to sense something from our worried faces. She asked:

- You look sad, what happened?

Varandian said: "Nothing, Avetis is supposed to come today, we've come to see him."...

Towards evening Aharonian arrived, his left cheek bruised... Varandian rushed at him, hugged him, started kissing him. When Mrs. Nvart saw Aharonian's bruised face - "Avetis, what happened?" - she exclaimed.

Aharonian began to tell:

- You know we had an event in Lyon. It turns out the Armenian Bolsheviks had brought Moroccan, Algerian, Italian communists, placed some in the upper boxes, the others near the entrance of the hall. When I went up to the stage and started to speak, that element shouted "Down with fascism!", then one of them rushed to the stage and attacked me, punched my left cheek with his fist; for a moment my hand went to my pocket (Aharonian had a small Browning pistol. A.A.), but I restrained myself; at that moment a few boys from our audience rushed to the stage and started beating the foreigner who had attacked me and brought him down from the stage. A few others surrounded me to protect me from further attack.

The hall was turned upside down, the seated audience started expelling the Bolshevik rabble, and near the hall door about two hundred people had clashes. Our people gave such a beating to the foreign attackers that they fled with torn clothes. The people's anger at that cowardly attack was great.

Varandian got up again, kissed Aharonian's wounded cheek, saying: "You can't imagine how worried André and I were, we didn't tell Nvart anything so she wouldn't worry."

That same evening we had a Central Committee meeting; during the Lyon clash, the police had arrested seven of our comrades. During the clash, a young Bolshevik named Baghdasarian had been killed (the "Yerevan" newspaper made a big fuss about "worker Baghdasarian"). It didn't take into account that the majority of the audience were workers.

It was decided that comrade Hrant Samvel, as a lawyer familiar with legal matters, would go to Lyon to hire a French lawyer to free our comrades from jail, and they sent me too, to encourage the comrades, raise their spirits.

Hrant Samvel left for Lyon, and I left a day later. The comrades had gathered in an upstairs room; when I entered, they all stood up and shouted in unison "Long live the A.R.F.!..." The morale was high. I spoke about the cowardly attack, in which the Armenian Bolsheviks had involved foreigners; but just as they learned their lesson in Paris, so too in Lyon and henceforth they will come to their senses. The Armenian masses are with the Federation, the Lyon event proved that.

My speech was received with stormy applause. During my speech, I saw that Hrant Samvel withdrew to the side room; later when I asked him the reason, he said that he had to deal with the court and perhaps the police to free the comrades; therefore his presence at that meeting could cause inconveniences... Hrant was very cautious.

A few days later, the police released the imprisoned comrades on bail; they couldn't find the perpetrator of the killing.

After that incident, the Bolsheviks didn't dare disrupt our events in the provinces anymore.

In those days, the poet Avetik Isahakian had come to Paris from Armenia on HOK business. The Ramgavars had written a circular regarding the Lyon incident and blamed Avetis Aharonian for it; Avetik Isahakian had also signed the circular... When Aharonian asked why he had signed, Isahakian answered: "I didn't read what was written, they said 'sign this circular'..."

*

We were having lunch at the "Prix Fixe" restaurant on Saint-Michel Boulevard. The lunch cost 3.50 francs, bread unlimited. Sometimes some Iranian-Armenian would come to Paris, I would take him to the museum, the promenades, and I was always the one spending; after that, for a few days I would eat on the street, with saucisson (sausage) made from horse meat sold standing up.

One evening, when we hadn't eaten anything all day, I was walking down from Saint-Michel with a comrade; when we were about to pass in front of the "Café de la Sourcé", Avetis Aharonian, sitting at a table in front of the café, seeing us, called out and said:

- André, your faces show that you haven't eaten anything today. Is that right?...

- That's right... I said.

- Well, come sit down, - said Aharonian and immediately ordered coffee with milk and croissants for us.

During the day I was busy attending lectures; in the afternoons I was in the library. I read voraciously. A little above Saint-Michel there was also a Russian library, where, they said, Lenin had also frequented. Both the French and the Russian libraries were very rich. At nights I read in my room. Those who wanted to see me knew they would find me in the library.

It was in the French library that I summarized the first volume of Karl Marx's "Capital" in a hundred pages of my notebook. I read writings about the anarchists Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin. The works of the famous Austrian theoretician-socialist Otto Bauer, the German Eduard Bernstein, E. David, the Italian anarchists Cafiero, Carlo, Costa, Malatesta. And I listened to the French socialists during their public lectures and speeches, mostly with my dear friend, the writer Vazgen Shushanian.

Sometimes it happened that members of left or right factions would burst into the hall of the socialists' lecture, make noise, disrupt; once they even broke the hall's mirrors and windows. I grabbed Vazgen Shushanian's arm and brought him out of the hall, saying, "We Armenians have given many losses, we don't need to give losses here too." Vazgen laughed in his own characteristic way and we left the hall.

4. ACTIVITIES IN THE PARIS-ARMENIAN COMMUNITY: PART 2 OF THE 1920s [B.]

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 14, October 29, 1986, pp. 16-17 (516-517).

We were sitting at the "Café de la Source" one day—Hambardzum Grigorian, Vazgen Shushanian, and I—when the poet Ostanik entered breathlessly, saying: "The writer Kostan Zarian has come from Brussels with his wife and daughter, they are sitting hungry in a hotel room; give me a few francs, I'll buy bread and cheese and take it to them, they are pitiful; Zarian is a great intellectual, in the past he collaborated with Siamanto and D. Varoujan in Constantinople..." We were moved, each of us gave Ostanik a few francs, he left.

In the following days, K. Zarian also started frequenting our café; we became acquainted. One day I asked him:

- Mr. Zarian, how did it happen that you came from Armenia and didn't return? He told the following:

- You know, I was invited to Armenia as a university lecturer. Once I went to Tiflis; on the return trip, in my train compartment, several Armenian travelers started complaining about their difficult economic situation. When the train reached the Alexandropol station, several Chekists boarded the train and, arresting the travelers in my compartment, took them off the train and to prison. Right then I decided in my mind to leave Soviet Armenia for a free country and, I succeeded, I came to Europe.

We weren't in a position to give money every time for K. Zarian to eat; so one day I said to Ostanik:

- Ask him, if I mediate for Kostan Zarian to contribute to our Boston monthly "Hayrenik" and receive an honorarium, would he agree?

Ostanik had spoken, came and said: he agrees.

I immediately went to Aharonian, told him what had happened and asked him to write to the editor-in-chief of "Hayrenik," comrade Rouben Darbinian, and ask for his agreement. The "Hayrenik" monthly paid contributing intellectuals twenty dollars per month as an honorarium, which would save K. Zarian.

Aharonian immediately wrote a letter; he too was touched.

Barely two weeks had passed when a letter was received from Rouben Darbinian; he had written to Aharonian that he would gladly accept Kostan Zarian's collaboration.

I myself informed Kostan Zarian about this, and he was very pleased. He started writing.

In the "Hayrenik" monthly, Kostan Zarian's "The Banquet and Mammoth's Bones," "Lands and Gods," began to be published, which aroused great interest. Later, drawing material from Rouben's memoirs, he wrote "The Bride of Tatragom," etc.

In Paris, the Soviet "Torgpred" commercial representative was the Bolshevik Simonik Pirumian. Visiting him were: Hamlik Tumanyan (Hovhannes Tumanyan's son), who had moved from London to Paris, and Ashod Patmagrian, who had moved from Berlin.

We noticed that Ostanik and Yeghishe Ayvazian started making lavish expenses; Yeghishe had bought a chapeau hat for one hundred twenty francs, which was a lot of money for an unemployed man. The same also for Arpiar Aslanian (one of the exiled students) and his wife, the writer Lass, who was "left"...

One day I expressed my suspicion to Hambardzum; I said that comrade Hayk Asatrian had told me in Prague that when he was in Berlin he had learned that certain Armenian students were receiving money from the Soviets, on the condition that after studying they would go to Armenia, and he even gave the name of Grigor Der Andreasian, who was one of my seminary classmates.

Hambardzum confirmed my suspicion.

One day Hambardzum told me that he had met Hamlik Tumanyan on the street, and he had said that students were paid twenty dollars a month, but we will pay you and André fifty dollars; talk with André.

I was angry that they wanted to make me an object of trade; my ideas were not for sale. I told Hambardzum to arrange a meeting with Hamlik.

Hambardzum got an appointment; we met on a street near the "Luxembourg" garden.

- Tell me, Hamlik, what were you going to say? - I said.

Hamlik started speaking negatively about the Republic of Armenia, and when he added that the Dashnak ministers... were stealing flour, I attacked Hamlik; Hambardzum intervened, Hamlik started running away with all his might.

- You shouldn't have let me go, I should have taught him a good lesson, - I said angrily to Hambardzum. "Let that much be a lesson to him," - said Hambardzum.

A few days later Hambardzum told me:

- I met Hamlik, he said: "If everyone were like you and André, we wouldn't succeed..."

It was already clear to us that the Bolsheviks were recruiting spies under the name of students. I went to the Bureau's room and explained the situation to comrades S. Vratsian, Rouben, and Jamalian and said that Y. Ayvazian and Ostanik must be expelled from our party group. The Bureau declared those two expelled with a circular.

The Bolsheviks convince Ostanik to go to Armenia; they will give him a recommendation and also cover the cost. They say: "You are a poet, you will go, they will promote you there..."

Ostanik leaves via Italy. Everyone already knew that Ostanik had left for Armenia.

One day we suddenly saw Ostanik in Paris...

The two of us entered a café. His first words were:

- André, you were right, I was receiving money; once I also received a check for one thousand two hundred francs from Ashod Patmagrian, besides the travel expenses. When I reached Italy, they had given me a sealed, recommendation letter to present in Yerevan. I was curious what was written in the letter, I opened it and what did I read? It was written: "Don't give this rascal the time of day..."

I immediately decided to turn back and here I told them that I was robbed on the way, my money and everything was stolen... You know it that way.

Two days later, Yeghishe Ayvazian met me and asked to enter a café. He also confessed that he had received money, that I had been right.

Although we forgave both of them, we didn't accept them back into the ranks.

Vazgen was a young man of medium height, full-bodied, with large black eyes, rosy cheeks, fair skin; we became close from the very first moment of acquaintance. He was one of the orphans of the April Genocide; he had spent years in orphanages, then was transferred to an orphanage in Armenia, finally came abroad, graduated from the Montpellier agricultural courses, but had practiced his profession little. He came to Paris, occupied himself with reading and writing. His material needs were taken care of by his orphanage friend Sepuh, who was in Egypt. He was interested in social sciences, was a warm socialist; that's why we were always present with him at the speeches of French socialists, which sometimes ended in fights, with disruptive actions by the right or left.

Late evenings, Vazgen and I would go out for walks on the illuminated boulevards or in the Luxembourg Garden, and Vazgen would recite his favorite piece from Misak Medzarents:

"The night is sweet, the night is voluptuous,

Anointed with hashish and balm,

I will pass the luminous path intoxicated,

The night is sweet, the night is voluptuous"...

Vazgen had a pure heart and pure character; the Bolsheviks couldn't subject him to material temptation either.

Sometimes, when Artsruni Tulian was with us, he would bother Vazgen; once he hit Vazgen in the back and ran away. "André, see, he's treacherous, eh, he hits from behind," Vazgen would say and laugh his characteristic full-chested laugh.

With Vazgen we also read from the works of famous French poets, sometimes reciting passages by heart from Baudelaire, Alfred de Musset, Paul Verlaine.

Behind the Saint-Michel square was the cave of the famous French Apaches (criminal class); it was Vazgen's favorite place, though dangerous. The poet Paul Verlaine, who was also a drunkard, had frequently visited the Apaches' cave, on whose walls he had written his name. Vazgen would zealously show Verlaine's and other poets' signatures and exclaim: "See, these poets loved the Apaches..." and he was delighted that he too was walking in the footsteps of famous poets.

When I first entered the Apaches' cave, the dry, stone walls and carvings left a heavy impression on me. We went down narrow, stone steps and entered a small cave, where there was a rough table and a few rough, backless stools. In the side small room-cave, 3-4 Apaches were sitting, who looked at us with furious eyes at first, then ignored us. Vazgen told me that the Apaches rob some customers right here...

We ordered beer, drank it, and went out. I, who had gotten a heavy impression upon first entering, now became a lover of the Apaches' cave and thereafter would sometimes say to Vazgen: "Vazgen, shall we go to the Apaches' cave?" He would be delighted and we would go; the Apaches already recognized us and didn't cast hostile looks.

"How is it that your last name is feminine—Shushanian?" I asked Vazgen one day. "I've heard from my parents that my grandmother was a very intelligent and influential woman, so our family decided to use her name as the surname," Vazgen answered.

Vazgen wrote his literary works and articles in a small café near the "Café de la Source." When I wanted to meet him, I would go to that café; in a corner, sitting at a small table, he would be writing, his handwriting also very precise.

Artsruni Tulian would sometimes argue with Vazgen about his viewpoints. Once, when I was sick in my room, at a meeting Artsruni had accused Vazgen for his viewpoint. They came to me to get my opinion. When I heard, I said: "The Federation advocates freedom of thought, speech, and pen. If a Federation member's viewpoints do not contradict political conduct, he is free to express himself. If he has a viewpoint different from the political conduct, then every Federation member can express his viewpoints at meetings six months before the General Assembly; if the General Assembly approves it, good. And if it doesn't, the viewpoint will remain in writing in the minutes, and he himself will submit to the decisions of the General Assembly."

Vazgen was satisfied with this statement of mine.

5. ACTIVITIES IN THE PARIS-ARMENIAN COMMUNITY: PART 2 OF THE 1920s [C.]

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 15, November 12, 1986, pp. 13-14 (557-558).

In 1927, they had wanted an activist from Buenos Aires (South America) to organize the region and found a newspaper. They had given my name. I told comrade Rouben that I was going to the homeland. I had told him about that, therefore I could not go to Buenos Aires. Rouben said: - "You are right, we will write to them that you cannot go, for health reasons. You must go to the homeland. Our connection with the homeland is already severed anyway."

They sent comrade Tadeos Medzadourian (a relative of Misak Medzarents); he stayed for a year on organizational matters, but he could not be an editor.

When my turn came to leave for Armenia (in June 1928), we spread the news that I was going to Buenos Aires, as an activist-editor (Medzadourian had already returned). I didn't even tell my closest comrades that I was going to Armenia; only Artsruni Tulian knew, because he had gone to the homeland and returned; we had participated together in the 10th General Assembly.

On the days of my departure, Vazgen came with a package in his hand, and handing it to me, said: - "We have been so close, accept this small gift on the occasion of your departure"... The gift was an autumn outfit. I was moved. "Vazgen, my dear, why have you made such an expense, it's heavy for you," I said. "Please don't refuse, it's a comradely gift," he said, and also gave me his picture.

Months later, when he had learned that I had left for Armenia and been imprisoned, in 1930, when I was exiled from the Soviet Union to Persia, Vazgen immediately wrote a letter, expressing his joy that I was free, and sent another picture as well.

I keep his picture to this day like a relic, on which is written in his handwriting: "To dear André from Vazgen", Paris.

Young people would sometimes come to Paris from the south of France, barely of medium height, with a round, plump build; Vazgen would say to me: - "André, look, eh, it's orphanage merchandise"... and, indeed, when we checked, they had been in orphanages.

Vazgen Shushanian made a name for himself in literary life and his writings are still read with pleasure to this day. What a pity that he died prematurely. I will never forget my dear Vazgen Shushanian and his sweet chuckle.

The A.R.F. Western Regional Delegates' Assembly was to take place in the city of Lyon. We had heard that Abo (Baghdasar) Aboyan had organized "fingers" and was going to make a speech against Eastern Armenian activists, with factional passion... This was discussed at the comradely meeting of the Paris committee, and I also made a speech, declaring that the Federation recognizes neither factional nor regional discrimination. Comrades Gerasim Balayan and Armen Sasuni defended my viewpoint and insisted on my candidacy as a delegate. With me were also Vazgen Shushanian, Mkrtich Yeretsian, Gegham (a poetry writer), Levon Mozian and another comrade whose name I have forgotten.

At the assembly, comrade S. Vratsian was present on behalf of the Bureau, who restrained himself. Aboyan had brought thirty-three organized "fingers", mostly from novice youths.

Every time Abo spoke, I would ask for the floor and neutralize the impression of what he said. The assembly had already gotten used to it and after Abo spoke they would say: - "Now André will ask for the floor."

From Lyon, there was an elderly comrade named Khakhosian, tall, with a dry and bony build, his eyes like marbles. During a break in the assembly, noise was heard from the corridor; when we went down to the corridor, they said that Khakhosian had slapped Vazgen Shushanian and they warned that Khakhos had a pistol. I was very affected that a vulgar Khakhosian had slapped a young comrade like Vazgen.

At the assembly, I proposed that Khakhosian be banned from attending for three sessions and that his weapon also be confiscated; the decision passed, but when it came to confiscating the weapon, no one made a sound; when I saw no one was speaking up, I volunteered. Everyone was impatiently waiting to see what would happen. I went to the neighboring room, where Khakhosian was sitting alone, sat down next to him and said: - "Comrade Khakhosian, for slapping comrade Vazgen Shushanian, the assembly decided to deprive you of three sessions, besides that, hand over your weapon to me."

Khakhosian, without a word, handed the pistol to me. When I entered the assembly and placed the pistol on the chairman's table, everyone was surprised. I said that comrade Khakhosian submitted to the instruction without resistance and proposed that the three-session punishment be reduced to two.

The assembly reached the point where Abo's organized thirty-three "fingers" disintegrated. Mesrop Guyumjian, who was Abo's right-hand man, asked me to go to the neighboring room. "Comrade André, please spare me," he said. "Comrade Guyumjian," - I said - "I have nothing against you, but Aboyan's conduct is divisive and I am against factional conduct, and you should be too."

In short, Abo was not elected to the Central Committee and left for Marseille with his nose down. I also withdrew my candidacy, first because I had to leave for Armenia, and also so they wouldn't say that I toppled Abo so that I myself would be elected.

When we returned to Paris, Gerasim Balayan and Armen Sasuni expressed satisfaction that I had neutralized the divisive Abo.

When I met comrade Rouben, he said: - "André, you got into a brawl in Lyon..." I told him what happened, Khakhosian's slap and the disarmament. Rouben was satisfied.

After my departure for the Soviet Union, Ashot Artsruni had a clash with Abo; Artsruni threw a bottle at Abo's head, wounding him.

It was after my departure that this movement was called "Martkots". They founded a newspaper in Marseille and exploited the name of captain Smbat Baroyian (Smbat from Mush - Andranik's comrade-in-arms), who was semi-literate. Shahan Natali had also joined that movement. In the end, it was confirmed that Abo had received money from the Bolsheviks, to split the Federation... Benik Miltonian had left Abo; Benik was a straightforward and pure personality, while Mkrtich Yeretsian and Levon Mozian, who were with me at the regional assembly, later went over to collaborate with Abo.

Abo, with his wife Zarmik (a gossipy and slanderous woman), leaves for Soviet Armenia on the advice of the Bolsheviks. One day the Cheka calls him and says:

"Repeat that speech of yours that you used to give when you were a Dashnak..." Abo is stunned and stammers. The speech was the following: "One day they ask Stalin, 'How do you lead two hundred million people of Russia?'. Stalin answers: 'They are two hundred million donkeys, whom I ride and drive...'"

Abo and his wife are exiled to Siberia, where he dies in misery.

One day at a comradely meeting in Paris, Shahan made a speech and declared: - "The Federation has become a stable..." I immediately asked for the floor and declared: - "I protest against comrade Shahan's expression. His words are outside the agenda as well, I demand he be interrupted." The chairman of the meeting and the attendees approved my protest and Shahan sat down in his place.

The next day I went to the Bureau's room; Rouben was there and I told him, upset, about Shahan's speech, adding that it was unbecoming of a Bureau member to compare the organization to a stable.

Rouben said: - "He has other things too, which we are examining. We will address that as well."

Gradually it was revealed that 1) Shahan, disregarding the decision of the General Assembly, had traveled first class by ship and train, wasting the party's money. 2) In America, he had secretly convened meetings with Western Armenian comrades, declared that Turkey must be destroyed by scientific means and collected funds, hiding it from the higher bodies. 3) He had joined the "Martkots" movement, carrying out destructive work, etc. 4) The Bureau had isolated him until the next General Assembly, for examination.

The General Assembly (the 11th) expelled Shahan from the Federation.

Avetis Aharonian's "My Book" (Childhood) was being typeset; I was proofreading it. Our leaders knew that I was an error-free proofreader. The typesetting of comrade S. Vratsian's work "The Republic of Armenia" began at the "Gukasov" printing house; the typesetter was Miss Satō, who was typesetting on a line-casting (linotype) machine and made few errors; at the end, when Miss Satō was typesetting the preface, I saw that comrade Vratsian had also mentioned my name as the proofreader.

I told Miss Satō not to typeset my name. The next day, when I went to the printing house, the preface was already printed.... Miss Satō said that Vratsian had ordered to definitely typeset my name.

The "Republic of Armenia" volume was published almost without errors. Comrade Vahan Hambardzumian said: - "You proofread more conscientiously than the author himself." I write about this because especially in recent decades the press and books are full of errors; the Armenian language has regressed; those who know orthography can barely be counted on the fingers of one hand... The books I authored, which I proofread myself, have no errors.

Vratsian wanted to pay me for the proofreading through Artsruni; I refused to have performed paid proofreading (I had proofread Aharonian's book for free as well). Artsruni Tulian later tricked me. He knew that I was going to the Homeland; one day he said: - "You are going to the Homeland, you need a raincoat (plashch). I didn't take one, I needed it badly." It occurred to me, we went to a store, chose a raincoat, Artsruni immediately ran to the cashier to pay; I caught up with him to pay my money, he stopped me, saying: "This is comrade Vratsian's gift, one doesn't refuse a gift..."

I must say that the clothes donated by Vazgen Shushanian and the raincoat donated by comrade Vratsian wore out in Soviet prisons....

6. A DASHNAK ACTIVIST IN MOSCOW IN 1928

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 21, February 4, 1987, pp. 11-15 (835-838).

Before my departure, I went to the Delegation to say goodbye to Alexander Khatisian. He also thought I was leaving for Buenos Aires, as an activist. He began to give me names and addresses of acquaintances who could be useful to me. "I have good impressions of you, as a young activist. You are the only one among those who borrowed money from the Delegation who has repaid it (Khatisian had also told Levon Nairzi about this, who told me)."

I was in an awkward position, where was I going, where did my comrades think? Khatisian's wife was Russian, very modest, polite and with a smile on her face; they lived in one room of the delegation; I said goodbye to Khatisian and his wife, and came out sweating.

When saying goodbye to Artsruni Tulian, I said: - "If I ever sign a declaration in the Soviet Union, remember Vartan Mamikonian. Also remember that I christened you with the name Ashot Artsruni, when you were looking for a suitable signature for your newspaper articles (to this day he still signs as Ashot Artsruni, it's been fifty years...)".

When parting, Ashot Artsruni said emotionally: "We will not meet again"... He knew the dangerous nature of my mission; he himself had come from the Homeland and from 1928 until today, 1978, we have not met each other, although we corresponded, he in Buenos Aires, I in Tehran.

I went with Rouben to Avetis Aharonian. In those days (the end of June 1928) Aharonian had suddenly gone blind while speaking with the French... Rouben said: - "Avetis, we are sending André to the Soviet Union. Can you give any address, via Moscow?" Aharonian was very moved. I was standing by his bed, Rouben was stroking Aharonian's forehead:

- Ah, it's a dangerous mission. In Moscow, go to the Armenian church, Armianski Pereulok (Armenian Lane). There is a respectable priest there, Father Arsen Simonian; he will give you the addresses of comrades," said Aharonian. He took my hand, squeezed it, we said goodbye with Rouben. (Later his eyes opened and he became the former Aharonian).

I said goodbye to comrade Vratsian in the Delegation building, kissed him, wished him success and he said: - "May I not be seen with you" and left.

I met Shavarsh Misakian, who was the treasurer of the Bureau; he gave one hundred fifty dollars, as a "loan"... I signed the receipt.

I left for comrade Jamalian's place, with my suitcase; I was to receive instructions there; then I was to leave by train. He lived in the suburbs, with his family.

Rouben was there. "Now you must memorize three ciphers, with the initials Erna, André and Arus. Erna is my daughter's name, and Arus will be your codename," said Jamalian and began to explain the secret of the cipher to me. I memorized the cipher on the spot. Later he said: - "I am giving you two passwords that we took from Dro; Tigran Aniev is located in Moscow, he was an officer in the Republican Armenia, and in Moscow he was also close to Dro; Aniev is a social-revolutionary although, but he is with us, a reliable one. You must tell him these passwords first, so that the comrades trust you. A. password: The torch of Lealeia, B. password: God and the forty devils are with us."

"Our comrades are exiled to Moscow: Koriun Ghazazian, Tigran Avetisian, Bagrat Topchian, Smbat Khachatrian, Arsen Shahmazian. You will meet them, but avoid meeting Bagrat Topchian, because we have heard that he recently has different views. You will report to the comrades about the current political situation, also about the decisions of the 10th General Assembly, which you yourself attended and participated in. You will also learn about their views, our policy to be pursued towards the Soviets. The Bureau authorizes you to neutralize unreliable comrades, even to dissolve a body if necessary and appoint a new body. Ask the Homeland's Central Committee what happened to Budashko's Thirteenth... also, we sent literature and money, have they received it?" said Jamalian. Rouben said: - "Tigran Gavarian is located in Alexandropol, he is one of our old fedayis from Taron and knows me well. You will see him, he will acquaint you with our comrades in Alexandropol. We are sending secret literature and money to Tigran."

Jamalian continued: - "You will work to establish a connection via Baku with our people in Persia, Enzeli. The last trial in Armenia has severed our connection and we don't know who remains now. Only in Yerevan, avoid Mihran Grigorian, he has given a declaration; he was a member of the Armenian parliament. Be careful, don't trust everyone, there are many Soviet spies."

Rouben said: "You will meet the Bolshevik Armenian leader Sahak Ter-Gabrielean and speak about Karabakh and Nakhichevan, that they work to annex them to Armenia; these are Armenian lands, it was an injustice to hand over those regions to Azerbaijan," and he began to explain the military significance of Karabakh, that modern Armenia is separated from Karabakh to the northeast by a mountain peak (Selim) and a mountain pass. He had written research articles about these regions in "Droshak", I had proofread them; the subject was familiar to me.

I told Jamalian and Rouben that comrade Vratsian had given the name of a doctor Sargsian, whom I was to meet in Baku, perhaps through him I would establish a connection on the Baku-Enzeli line. After talking about a few more details, I said goodbye to Jamalian, and Rouben and Jamalian's fifteen-year-old son, Armik, who was very attached to me, came to the train station to see me off. We kissed. When I boarded the train, I turned back to say goodbye, and saw that tears were flowing from Rouben's eyes... This was our last parting, I was not to see him again.

*

Comrade Jamalian had ordered that I not take any papers or books with me; I had told him that I had a French book by Lenin - "Imperialism as the Highest Stage of Capitalism" and a small pocket dictionary from French to Russian. Jamalian had said not to take the Lenin book with me, it could cause suspicion, so I threw the book out of the train window, but kept the dictionary. In my suitcase were only my clothes. I had taken a transit visa from the Soviet consulate in Paris; in those years, a traveler had the right to stay twenty-four hours in every main city.

In those days, the Vakhtangov-named acting troupe had come from Moscow to Paris, I had attended one of their performances; and so, when our train stopped at the Berlin station, the Vakhtangov-named actors' troupe boarded the train and filled the compartments near me. Suspicion crossed my mind, so I decided to show that I didn't know Russian, and also to get off in Warsaw for two days (Jamalian had also said this, if I saw something suspicious on the way).

In Warsaw, I checked into a hotel. I went into the city, bought a Russian-style blouse, a cap; in Moscow I was to walk around in that clothing, so as not to arouse suspicion, otherwise European clothing would attract attention and suspicion. I had a breastplate button with the picture of Kristapor Mikayelian, which comrade Hmayak Poghosian (the elder brother of comrade Tachat Poghosian) had given me back in Tabriz in 1922, when I was leaving for Armenia; I couldn't have that insignia with me; my hand didn't go to throw it away either, so I put it under the outside tin of the hotel window, where it could remain safe for a long time. When I was about to leave the hotel, five attendants stood in a row... I was supposed to give a tip, whereas I had only seen one of them. I gave a tip and left for the station.

At the border of the Soviet Union, I got off, they looked at my suitcase, I passed.

*

At the Moscow station, I put a set of underwear in my portfolio, my shaving kit; I had changed my clothes. Ashot Artsruni had told me that Soviet officials and Chekists wore a blouse, put a cap on their head, and carried a portfolio; I had dressed like that too. I checked my suitcase at the station, took a carriage. I ordered to go to Armianski Pereulok (Armenian Lane [alley]), where the Armenian church was located. The carriage looked very wretched, two emaciated horses, the inside upholstery of the carriage torn, hanging, the coachman, an old Russian, emaciated like his horses... Moscow in those days, after Paris, resembled a large village.

In the carriage, my heart was pounding, - "But what if I didn't see Father Arsen that Aharonian mentioned, what would I do without meeting comrades in Moscow..."

I arrived, got out of the carriage, entered the church courtyard, opposite was the church, on the left wing wall there were two doors, clean, made of chestnut wood, I knocked on one door, a young woman with a beautiful face opened the door.

- Excuse me, can I see Father Arsen? - I said.

- Wait a moment, - said the woman and went inside.

I breathed a sigh of relief, so I had found Father Arsen.

A priest with a pleasant face appeared at the door.

- Father Arsen, I am coming from Paris. Avetis Aharonian sends you warm greetings. Recently he lost his sight for three days, but, fortunately, regained it. Please give me Smbat Khachatrian's address.

Father gave the address, was happy about Aharonian's greeting and health. I said: "Father, after Paris, Moscow resembles a large village," he said: "It's better now, you should have seen it five or six years ago - what it was..."

When saying goodbye, I said, "Father, neither have I seen you, nor you me." - "Of course, my child, welcome," he said, I left.

Seeing the Moscow Armenian church, I remembered what Aharonian had told about the terrorist act of the bell-ringer's thirteenth, which had taken place in the courtyard of that very church.

"The terrorist was from our barely writer young comrades, had taken refuge in Geneva, had become very attached to me. The Armenian millionaire bell-ringer was subjected to a terrorist act by decision of the Federation, because he had betrayed the collection of money for 'Storm' to the Tsarist Okhrana," Aharonian would recount.

The Moscow Armenian church belongs to the Lazarian seminary, whose building I saw from the outside.

*

I went to the address given by Father Arsen, in the entrance hall on a blackboard was written in chalk in Russian: house committee, on duty: Smbat Khachatrian. I went up the stairs, knocked on the first-floor door, the middle part of the door was made of leather, stuffed with wool... Undoubtedly, to protect from the Moscow cold. I knocked several times - no one opened. I thought I'd go away, come back a little later, maybe he had come.

On the street I saw a barbershop, went in. Two soldiers were waiting in line, I also sat down. My clothing was such that they wouldn't suspect. When my turn came, the talkative barber began asking questions.

- Where are you from, citizen? - he asked.

- From Leningrad, - I said.

- How much does bread cost? - he asked.

I had followed the Soviet press in Paris, so I named a price.

- How much does meat cost?

Again I named a price.

- Is it your first time in Moscow?

- No, I passed through Moscow to Leningrad, - I said.

Finally, the haircut was over, he wanted to shave my face, I didn't let him; to free myself from new questions, I paid, came out sweating... I quickly moved away towards S. Khachatrian's apartment; he wasn't home again...

I took a carriage to the Armenian church, to Father Arsen.

- Father, comrade S. Khachatrian is not home, I went twice, knocked on the door - Oh, today is Sunday, probably he went to see acquaintances. Do you want me to give you Bagrat Topchian's address? - he said.

Although comrade Jamalian had said "Try not to meet Bagrat," but since Father Arsen mentioned the name and I had no other address, I said yes.

- He lives with his wife in the building of the Moscow Armenian cemetery. Only be careful when entering, the doorman is a Russian spy, - said Father Arsen.

I said goodbye, took a carriage to the Armenian cemetery.

The cemetery door was a large iron grating; I saw a little girl behind the door playing with a ball:

- Dear girl, is Uncle Bagrat home? I asked in Russian. She said yes.

- Well, open the door, - I said.

The girl opened the door, I entered; I saw on the left side, about fifty steps away, the Russian doorman was sitting on the steps of his hut, with his family. I quickly passed to the right, near the trees, towards that one-story building in the cemetery where Bagrat lived. I had seen Bagrat in Tiflis in 1917-1919, his face was familiar to me.

I knocked on the apartment door, it opened. It was him, I recognized him.

- Comrade Bagrat, I am coming from Paris, I must meet you with important assignments, may I come in?

Bagrat silently let me in. I sat on a chair, he went behind his desk, began eating blini (broth from dough), silent and thoughtful. I understood him, he was in doubt, so I said.

- I have passwords about Tigran Aniev, so that you trust me; until then you can say nothing to me.

Bagrat's facial expression changed.

- I have seen you in Tiflis, heard your lectures, also comrades Vahan Soreni, Koriun Ghazazian, Tigran Avetisian. I must also meet comrade Koriun and T. Avetisian, - I said.

- Koriun and Avetisian are in a prison in the Urals, - he said.

- In that case, I will speak and report to you, comrades Arsen Shahmazian and Smbat Khachatrian; I went to Khachatrian's apartment, he wasn't home, - I said, - I took his and your address from Father Arsen.

Then I told that the Bureau's connection was severed, as a result of the trial and imprisonments of Manuk Khushoyan, due to the betrayals of the provocateur Budashko.

- Budashko came here from Paris, sat in the very place you are sitting, I knew he was a spy, we had sent news to Tabriz to inform the Bureau about him. I kicked Budashko out, declaring that I don't deal with party matters, he left, went away, - said Bagrat.

- Now I must establish a connection through your comrades here and those in the Homeland, can we go to Tigran Aniev? - I asked.

- Not possible now, it's daytime, we will go in the evening, - he said.

- In that case, let me ask one thing, the Bureau gave me ciphers that I memorized, I should give those ciphers to you before it's time, because if I am arrested, my mission will be in vain, - I said.

- Wait, I will come, - said Bagrat and went out of the room.

Barely ten minutes later he returned with a lively young man whose name was Kolik. He was wearing a Russian white blouse. We became acquainted, went to the back room, I quickly wrote the three ciphers, also the address given by the Bureau and said, - Comrade Kolik, take this away from here immediately, neither have I seen you, nor you me.

- Very good, - said Kolik, and putting the paper in his blouse sleeve, immediately left.

Bagrat no longer had any doubt, he asked:

- Didn't Tabriz inform the Bureau about our sent news about Budashko?

- Unfortunately, the news arrived two months late, when Budashko had already left Paris, - I said.

Then I told how Budashko had betrayed and exposed the secret line of the SRs (Social-Revolutionaries) via Finland to the Soviet Union. But Bagrat and the Moscow comrades knew about the betrayal and trial, prisons and exile of our comrades in Armenia. That was why the connection was severed.

*

When it got dark, Bagrat said let's go to Aniev's place, where I was to say the passwords.

Tigran Aniev was tall, somewhat dark-faced, with a likable face, one of the former officers, exiled to Moscow. Bagrat left me and Aniev alone in the room. I said the first password: The torch of Lealeia. Aniev thought, then said:

- I don't remember...

I felt awkward, so they will suspect me, I thought.

Just at that moment, a dark, small girl ran in with a ball in her hand...

- Ah, I remember, - exclaimed Aniev.

- Comrade Aniev, you saved me, I said, - otherwise...

As it turned out, Lealeia was that very girl's name...

- God and the forty devils are with us, - I said.

- Dro! It's Dro! - exclaimed Aniev and went to the neighboring room.

Then I saw comrades enter the room: Smbat Khachatrian, Arsen Shahmazian and Bagrat Topchian. I understood that they had been waiting in the other room, that if I were suspicious, they would let them leave, and if reliable, they would come in.

I conveyed the Bureau comrades' greetings to them, then reported about the 10th General Assembly and party life. The severance of the connection with the Homeland, the destruction caused by Budashko's actions, etc.

I also said that although I had taken a transit visa, in Yerevan I would apply to stay, I had performed one part of my mission here, the other part remained.

Then only Smbat Khachatrian spoke:

"We are grateful for the information you provided; you have fulfilled your duty 90 percent, therefore we ask that you do not stop in Armenia, go directly to Persia and report the following on our behalf to the Bureau:

1) Dissolve, abolish our secret organization in Armenia, because many comrades are being imprisoned and exiled, families are left helpless; whereas if those comrades remain in Armenia, they will influence the surroundings with their mindset, and the families will not be left destitute.

2) The Armenian Bolsheviks in Armenia have already begun to do what we would want; therefore there is no need for a secret organization," concluded his speech comrade Smbat Khachatrian, again asking that I pass through Persia.

I said my last goodbye to them, returned to the Armenian cemetery with Bagrat.

Bagrat's wife, Mrs. Ania, was a pleasant person; when she asked my name, I said: Anonymous. At first she was surprised at such a name, then it seems she understood, after that she would say with special emphasis: Mr. Anonymous...

At night, they assigned me a bed in the third, unfurnished, empty room and locked the door from the outside.

*

The next day, in the morning, comrade Bagrat said: - "Today at noon we will have a meeting of the Central Committee; you will become acquainted with the members, you will report and then you will hear their opinions."

At noon they came: comrade Mrs. Heghine Medzboyian, Kolik (whom I had seen the previous day) and Vardoyian; these two were my age, while Mrs. Medzboyian was elderly.

When comrade Bagrat introduced me to Mrs. Medzboyian, I said: - "You were a teacher in Tabriz in the past, isn't that so?" - "Yes," she said. "My mother, Yeranouhi Melik Vardanian (now Der Ohannessian) was your student and told me about you, I am the son of a student who loved you very much, from Tabriz" - I said.

Mrs. Medzboyian was moved, her face brightened,

"I remembered your mother, she was a petite girl, very fond of reading, I am glad to meet you," - she said.

Bagrat said that comrade Martiros Zarutian had sent word that he could not come, he always has a reason... (perhaps that's for the best, I thought, if we are caught, at least he will remain free).

Mrs. Medzboyian presided at the meeting; she impressed me, that intellectual comrade, with her sharp and brief speech; she was also exiled to Moscow and under surveillance.

I reported on the political situation, the decisions of the General Assembly, organizational life, the severance of connection and other issues. They listened, and Mrs. Medzboyian also repeated that I had fulfilled my duties 90 percent, that I should pass through Persia, to keep the Bureau informed about their and the homeland's situation. They live with great deprivations, and the party has no material means either. As for the connection by ciphers, the Bolsheviks now examine letters also by chemical means. Connection through live people is more convenient, like mine.

When the others left (this was also the last goodbye with them...), Bagrat told me:

- Tigran Gavarian, that fedayi from Taron, is now suspicious; secret literature and money were being sent to him from Tabriz, but he didn't give it to any comrade; now all our comrades in Alexandropol have been imprisoned and exiled, except for Gavarian... Do not go down to Alexandropol at any cost.

- I have an assignment about Budashko's terrorist act, - I said.

Bagrat became very angry:

- Enough! Enough! - he said, - we already did one, we saw what happened...

- Which one? - I asked.

- Jemal's, nearly six hundred comrades were displaced, one part in the Urals prison, the other part in the depths of Siberia, - said Bagrat, and added, - we have heard that Budashko is in Tiflis, do not go down to Tiflis either.

I listened to Bagrat, but in my mind was the Bureau's instruction, I had to settle the score with Budashko, but I didn't tell Bagrat about this either.

In Moscow, I had fully carried out the Bureau's instructions, handed over the ciphers and the address, reported and heard their views, so I left Moscow, having stayed there two days (July 4-6, 1922).

7. ARRIVAL IN YEREVAN AND ARREST

DROSHAK, 16th year, No. 23, March 4, 1987, pp. 11-15 (923-925)

From Moscow - on the way to Baku, I lay on the second, hay mattress of the train, my face towards the wall, so as not to be noticed by searching eyes.

At a station in the Northern Caucasus, when the train stopped, several armed mountaineers boarded the wagon and demanded that the passengers stand up;

we stood up, they looked at us in turn with furious and sharp eyes. Later we learned that they had taken two people off, as suspects...

I arrived in Baku early in the morning. I went by carriage to my maternal aunt's daughter's place. It was 6 in the morning when her husband, Boris, opened the door, remained astonished, "André, you here?"... "Yes, I came to see you and Perchik, I am going to Yerevan," - I said.

It was evident that both were afraid. I reassured them that I was going to Yerevan, to our family, I wanted to see them too after years of separation. The husband and wife were doctors, non-partisan, settled in Baku, had a two-year-old son, a Russian nanny came to look after the child during the day, they went to work. I instructed them to tell the nanny that I came from Moscow. During the day I also spoke Russian with the nanny, I had said I came from Moscow.

Comrade S. Vratsian, I wrote, had given the name of a doctor with the surname Sargsian, whom I was to meet in Baku; I asked Boris if there was a doctor with the surname Sargsian in their hospital; he said:

- There are two doctors with the surname Sargsian, which one are you talking about?

- I don't know the first name, - I said and the matter closed in this way...

We had other relatives in Baku; Mkrtich Karapetian and Grigor Nikoghosian, who had been a typesetter in Tabriz. A message was sent to Grigor, he came in the evening (they were children of my maternal aunt with my mother).

Grigor recounted that he was still a typesetter and as a worker his condition was not bad; but his brother, Mkrtich, who was a tailor, was dissatisfied and said that he would not remain in this country, he would go to Persia, to settle in Enzeli.

- Are you the former Grigor or not? - I asked.

- I am the former one, but now here I am called non-partisan, - he said.

- If I stay in Armenia, will you keep in touch with me?

- Of course, especially since we are relatives, - he said.

I thought: Mkrtich, who is going to Enzeli, will keep in touch with his brother Grigor, and Grigor with me.

I wrote an open letter to Paris, to Mshod Artsruni, so that he would know that I had reached Baku; he would inform the Bureau. I signed: Arus, this codename was known to them.